My article on Max Jacobs’ treatise on Nature Boy Buddy Rogers and his major contribution of the introduction of “sequencing” to pro-wrestling was published in the PWHF program/magazine for its 2015 induction ceremonies. I am posting my original draft here for those fans interested in the history of wrestling and learning how the game evolved into what it is today.

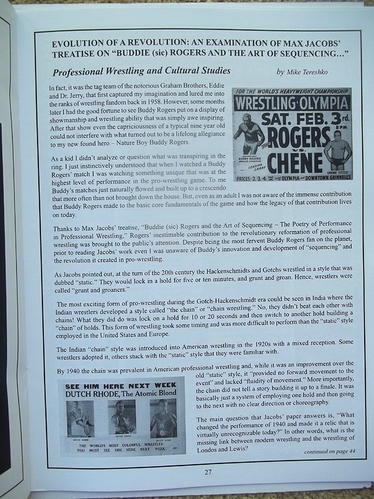

EVOLUTION OF A REVOLUTION: AN EXAMINATION OF MAX JACOBS’ TREATISE ON "BUDDIE (sic) ROGERS AND THE ART OF SEQUENCING…"

by Mike Tereshko

Although it was the notorious Graham Brothers who first lured me into the ranks of wrestling fandom in 1958, I later I had the good fortune to watch Buddy Rogers put on a display of showmanship and wrestling ability that was simply awe-inspiring. After seeing him, even the capriciousness of a typical nine year old could not interfere with what resulted in a lifelong allegiance to my new found hero – “Nature Boy” Buddy Rogers.

As a youngster, I didn’t analyze or question what was transpiring in the ring. I instinctively understood that when I watched a Buddy Rogers’ match I was watching something uniquely at the highest level of performance in the pro-wrestling game. Buddy’s matches naturally flowed and built up into a crescendo that more often than not brought down the house. However, even as an adult, I was not aware of the immense contribution that Buddy Rogers had made to the basic core fundamentals of the sport and how the legacy of that contribution lives on today.

Thanks to Max Jacobs’ treatise, “Buddie (sic) Rogers and the Art of Sequencing – The Poetry of Performance in Professional Wrestling,” Rogers’ inestimable contribution to the revolutionary reformation of professional wrestling was brought to the public’s attention. Jacobs wrote this term paper for his American Theater class as part of his Master’s Degree at New York University. Prior to reading Jacobs’ work, I was unaware of Buddy’s innovation and development of “sequencing” and the revolution it created in pro-wrestling.

As Jacobs pointed out, at the turn of the 20th century the Hackenschmidts and the Gotchs wrestled in a style that was dubbed “static.” They would lock in a hold for five or ten minutes and grunt and groan. Hence, wrestlers were called “grunt and groaners.” The most exciting form of pro-wrestling during the Gotch-Hackenschmidt era could be seen in India where the wrestlers developed a style called “the chain” or “chain wrestling.” No, they didn’t beat each other with chains! What they did do was lock on a hold for 10 or 20 seconds and then switch to another hold building a chain of holds. This form of wrestling took some timing and was more difficult to perform than the “static” style employed in the United States and Europe. The Indian chain style was introduced into American wrestling in the 1920s with a mixed reception. Some wrestlers adopted it, others stuck with the static style that they were familiar with.

By 1940 the chain was prevalent in American professional wrestling and, while it was an improvement over the old static style, it “provided no forward movement to the event” and lacked “fluidity of movement.” More importantly, the chain did not tell a story building it up to a finale. It was basically a system of employing one hold and then going to the next with no clear direction or choreography. The main question that Jacobs’ paper answers is, “What changed the performance of 1940 and made it a relic that is virtually unrecognizable today?” In other words, what is the missing link between modern wrestling and the wrestling of Londos and Lewis?

The answer is a system called “sequencing” that was invented and developed by Buddy Rogers. Contrary to chain wrestling, sequencing creates and choreographs a story from beginning to end. In sequencing each series of holds and maneuvers builds up to some sort of conclusion as a part of the whole match. Each subsequent series of moves and holds increases in intensity from the previous series. This sequential building of intensity and story line culminates in the finale which is the apex of the match and is designed to bring down the house. Jacobs points out that the development of in-ring work in the form of sequencing was only one of Rogers’ areas of innovation. As he was developing his persona he switched from face to heel in the mid-1940s. One reason was money – a good heel made more than a good face. Equally important was the fact that the role of face constrained his use of sequencing and the choreography of the match. As a face, Rogers could only react to the heel’s dirty tactics and had to be wary of not damaging his good guy image. As a heel, he controlled the sequencing and could do whatever he wanted to further the story and antagonize the crowd.

Jacobs describes Strangler Lewis’ advice to Rogers when Buddy became overly absorbed with his entrance and pre-match act. While watching a Gorgeous George match together, Lewis told Buddy that they could leave after George’s entrance and pre-bout antics because that was all there was to see. The match itself was a non-event. What Lewis meant was that it is still all about the match. The peripheral stuff is icing on the cake. And that was one of the big differences between Buddy Rogers and Gorgeous George. George’s pre-bout antics were it. The match itself was irrelevant. Rogers’ main effort was always crafting a match that was a work of art. The strutting, scowling, and antagonizing the crowd was just a prelude intended to create heat that would get them in the right mood for the bout itself.

The Max Jacobs’ paper is an eye-opener that delves into the career and life of Buddy Rogers and is recommended reading for any wrestling fan who is interested in the history of the game and how it developed. Buddy Rogers had one of the greatest wrestling minds in the history of the sport and is significantly responsible for the wrestling’s evolution!

A few sidelights learned from the Jacobs paper:

-

Buddy had a brother (unnamed in the article) that was nine years his senior. He was an amateur wrestler and practiced with little Herman Rhode (Buddy’s birth name) and became proficient at it. His brother turned pro in the early 1930s during the Depression to earn money for the family. In his sixth professional match, his leg was accidentally broken by Jumping Joe Savoldi. From that point on, his brother focused on Buddy preparing for a wrestling career.

-

Buddy’s first match was in 1940 at the Garden Gate Pier in Atlantic City, NJ. He wrestled there for a while but was only averaging $5-$8 per match. He went to work for the Dade Brothers Circus where he played the “local” shill who pinned the circus’ strongman/wrestler, hence encouraging the local yokels to put down their money and take a shot at the wrestler Buddy beat. (Of course, the locals got their derrieres kicked, but that was the idea!) In his first year or so, Buddy wrestled under the name “The Punk.”

-

According to the term paper, Buddy married at 19 for the first time and had four other wives over the course of his life. He had a daughter and a son named David.

-

In 1943, Buddy’s career took a turn for the better after Joe Cox became his trainer and also did some managerial work for him. He convinced Buddy to get out of New Jersey. The four Dusek Brothers controlled wrestling in the state under the name of “The Riot Squad” and were violent heels in and out of the ring. They weren’t going to let a “pretty boy,” i.e. babyface, local kid get anywhere on their turf.

In 1943 and 1944 Cox got him matches elsewhere, including a bout with Ed “Strangler” Lewis who took a shine to Rogers after shellacking him in that match. Lewis introduced Buddy to Jack Pfefer who, despite his personal idiosyncrasies, knew how to handle the business side of wrestling. At first, Pfefer was leery of Rogers because Buddy spoke fluent German that he learned from his parents. Pfefer would talk in Yiddish when he didn’t want his wrestlers to understand what he was saying. Yiddish was a mixture of German and Hebrew that Eastern European Jews spoke and was perfectly understandable to German speaking Rogers.

-

Buddy trained Billy Darnell and helped to turned him pro. He taught him sequencing and Darnell became one of his favorite opponents. He was Buddy’s “glove” according to the article.

-

In 1951, Buddy broke up with Jack Pfefer. Rogers was emotionally upset about the split because Pfefer had taught him a lot about the financial end of the business. Unfortunately, Rogers felt that Pfefer was causing more problems than he was worth at the time of the break up. Rogers told Jacobs that both men were in tears when the broke up. Finally, on September 6, 1962 Karol Krauser and Bill Miller cornered Rogers in the dressing room and broke his arm. Buddy had them both arrested. Pfefer reportedly had paid them $1,500 for the “hit.”